TRIPLE AAA

Contributing artists: Chance Collective, Heidi Harrison, Ellie-Lea Jansson, Justine Bootsorion Keim, Lisa Kelly, Nadia Milford, Katherine Morrice, Ashley Peel, Renee Poli and Juno Toraiwa.

SHOWCASE DOCUMENTATION

Click through to view event and artwork documentation

Photos by Joseph Lynch, Perception Productions

TRIPLE AAA HIGHLIGHT REEL

Triple AAA: In No One’s House

Indy Doumenc-Medeiros,

The Red House, Brisbane 2019 On Friday 22nd and Saturday 23rd of February 2019, House Conspiracy showcased the work of ten independent artists and collaborators in an exhibition called Triple AAA. The exhibition was grounded in a curatorial philosophy conceived by co-curators and exhibiting artists Ellie-Lea Jansson and Lisa Kelly.

The acronym Triple AAA stands for the three central conceptual tenets of the exhibition: architecture, archaeology and archetypes. Across all works, the Body was analogised through one or more of these concepts; as a structure to be habited, as a past to be unearthed or as an identity to be worn. Unspoken, intuited psychic realms was also a prominent theme, which can be interpreted archaeologically, as digging deeply within oneself for this hidden dimension, as well as architecturally, as a structure within oneself to study and inhabit. Chance Collective created a conceptually and comprehensively pink installation to posit a concise question and philosophy. Nadia Milford’s movement and installation work M A I D embodied and explored the cultural, philosophical and psychological significance of the Mermaid archetype and empowered femininity more broadly. Justine Bootsorion Keim’s multimedia installation Drawing Down the Moon similarly encapsulated the audience into her externalised mind, however she did so without reference to an external or historic identity. Heidi Harrison’s roving work did use a historical figure to at once dilute and revivify stagnant notions of inside and outside. Juno Toraiwa’s movement piece blended archetypal embodiment with personal exploration into an emotive improvisation that reached well beyond the walls of the house. Venus Figures: Portraits of Recovery by Lisa Kelly sought the power embedded in iconic feminine forms of history, and revisited them as sources of personal reparation. Katherine Morrice’s suite of portraits is as much about unearthing what lays beneath the skin as it is about emulating it. In parallel, Ellie-Lea Jansson’s video work documents the artists’ own subversion of disempowering domestic spaces. Renee Poli’s performative/sculptural work soda rot riot questioned what tangible and intangible materials constitute a built environment. However, rather than making direct reference to an archetype, Poli coaxed character into her work via the experiences her audience created by moving through the work themselves. Likewise, the R.E.S.P.E.C.T: Times Have Changed mural by Ashley Peel was built into the flesh of House Conspiracy, which manoeuvred people’s thoughts as much as it did their steps. These conceptual threads echoed throughout House Conspiracy in an eloquent and coalescent curatorially bind that drew ten minds into harmonic dialogue. Over those two days Triple AAA actioned a paradigm shift in which the domesticity of House Conspiracy fluctuated between criticism and redefinition. This transition refracted throughout the works into a wholistic reconceptualization of what the body is, what a house is, what any structure is, and how it can be transformed, repurposed and used.

CHANCE COLLECTIVE: Nest

Nest was an interactive, audience driven, multi-media installation. The participatory demand of Chance Collective’s theatre is a necessary mode of delivery, as it is more conducive to audience members engaging with the ideas of each particular work, rather than receiving them passively. Central to this piece, and reflected in their diverse use of textures and experiences, was the question ‘What is Femininity?’ Rather than positing or fostering a particular answer, the installation was designed to prompt curiosity, discussion and fun. This affirms the ensemble’s ethos which is so central to their broadening creative repertoire. The installation was decisively lo-fi and pink, immediately separating it from anything outside of itself. Pink tinsel curtained the entrance, pink cleaning appliances, technology and fixtures furnished the room. Pink foil and plastic coated the ceiling and walls, making the room feel like both an organ and a spaceship.Some of the Collective’s members took turns to lie on a table in the middle of the room beneath a veil, sparsely clothed. This was a beautiful echo of Juno Toraiwa’s movement piece which took place intermittently in the adjacent room. The veiled bodies’ slowed paces became sculptural and her isolation vulnerable. Yet she was also a live and constant manifestation of femininity, necessary within the body of the installation. The heart, a strong muscle. Other interactive features of Chance Collective’s immersive room were a mobile phone which rang occasionally, the screen instructing audience members to ANSWER ME. A hand sat in a box wearing a pink washing glove, open and waiting to engage with another in ungoverned action. There were empty pink eggs participants could smash, perhaps a witty satirisation of aggression and impotence. There was a live feedback the audience could watch of themselves moving around the space, and other video work of Collective members graphically preparing a whole raw chicken. By sensorially overloading their installation, Chance Collective commanded a fierce and intersectional repurposing of space, thought and action.

Chance Collective members are Olivia Brand, Victoria Barlow, Siobhan Gibbs, Zoe Sheppard, Milly Walker and Honor Webster-Mannison.

HEIDI HARRISON: In the Mood for Dreaming

Heidi Harrison and her performers each transcribed their dreams and then collated them into one body of text. The result was akin to a collective dream, which they then embodied in Butoh and Dairakudakan informed movement. This practice sought to touch a psychic that sits beneath our waking lives, and to translate it through bodily movement into this shared reality so we may come to remember its presence in ourselves. Harrison’s piece was inspired by Sir John Everett Millais’s Pre-Raphaelite painting Ophelia, 1851-1852, a painting that takes its namesake from Shakespeare’s Hamlet. In this durational and roving performance, Harrison adopted the guise of Ophelia in a body of water while her performers become moulds or ‘igata’, statues in motion. The kitchen of House Conspiracy was converted into a garden with a bath-pond, costumed with primeturf and fake flowers, and performers roved in and around the various spaces of the House. On the second showcase night, the roving performers amplified Harrison’s conceptual blurring of inside from outside by offering their bodies as canvases to Renee Poli in the garden to perform her spray-painted poetry. Harrison’s piece can be considered a translation, a transfer of meaning over time and medium. Millais’ Ophelia is a woman floating along a stream, flowers surrounding her delicate frame, subsuming her into her surroundings. Without Shakespeare’s text or knowledge of it, we do not know that this woman, Ophelia, was a pained and pining lover, drowned as much by her own woe as by her ill fate. But by referencing Millais’ emulation of Shakespeare’s character, Harrison’s piece is bound only to what Millais painting itself conveys of Shakespeare’s original character. By Harrison becoming the Ophelia painted by Millais, Shakespeare’s Ophelia has been reincarnated through her movements. Translation creates new meanings as much as it harbours old ones.

ELLIE-LEA JANSSON: Safe Space

Ellie-Lea Jansson’s documented performance work revised the prescribed function of domestic spaces such as kitchens and bathrooms. These functions have often been treated as feminine, primary and mandatory, and so become injurious to those who incur them. Jansson used particular props such as knives and bleach as a metaphor for the danger posed by domesticity. It is something that can stain, bleed or kill off psychic energy that would otherwise be purposed to creative, physical, or personal ends. By using these rooms and their contents as a stage, Jansson created her own necessary psychic space in the face of the domiciliary repression they imply. Jansson’s video was projected above the same table which Juno Toraiwa used for her performance during the times Toraiwa was not performing, which emphasised the shared symbols of domesticity in the two works. Jansson provided conceptual support to Toraiwa during the development of her piece, so the table is a comfortable location for the two pieces to be so intertwined. Rather than doing a live performance, the simple act of recording changed her actions the power dynamic of Jansson’s video work. The video is a document of autonomous movement that was not muddied by the context of its production: it was not done for an audience but for the artist herself. Furthermore, video recording meant the artist could erase the soundtrack, thereby obscuring the rhythms which guide and inform her movement. Jansson is driven and motivated by something outside of the room, but something to which the audience is not and may not be privy. By recording her performance, Jansson affords herself an opportunity to be decisive about how much the audience is allowed to know. She is giving herself permission to exist for herself only, on no one’s terms and in no one’s house.

JUSTINE BOOTSORION KEIM: Drawing Down the Moon

Justine Bootsorion Keim’s immersive performance was the realisation of her inner world come to light, or rather, her inner world come to light and dark. An adventure into her the architecture of her psyche. A myriad of media furnished her performance space under the house, which looked like it had been pulled from a David Lynch dream, if David Lynch were a High Priestess. One of the main and immediately perceptible features of the installation was the use of lighting. Keim manipulated light so she was able to interact with the shadows that emerged from the environment, not against or around them. The metaphor of literal shadow to psychic shadow was apt and articulate, allowing the audience to understand and be immersed in Keim’s mind-world. Shadow is a medium that balances between two realms: dark and light, visible and invisible, present and absent, realised and unrealised. Thusly, shadow is a vehicle to a similarly balanced realm that sits between reality and dream. Smoke mixed with plumes of chalk, which were released from a crucifix which Keim stood over and intermittently busied herself compulsively redrawing, adding to the mystic atmosphere. Paintings in the installation similarly engaged with obscuration. They depicted scenes of the construction site opposite House Conspiracy on Mollison street. These images were captured from a fleeting vantage point, as the scenes they depicted are daily being cased in concrete and high-rise living. Just as the presence of light obscures darkness, the presence of visually striking structures will threaten to eclipse the history of the site they impose. Sound was also prominent in the installation. A fox-headed man in a dishevelled suite sat in the corner reading a newspaper which he substituted for an electric guitar, eerie and reverberating. Keim moved to these warped sounds, answering their call with her own screams and wails. It’s not clear who was responding to whom, the moving body to the sound or the sound to the body. The result is the dissolution of creative domination and the emergence of harmonious, symbiotic influence. Keim’s sparse white costume was a prominent choice in an installation cast in shadows. In a literal sense, it makes her the greatest conductive surface of light in the room. In a performative sense, she is the Conductor of our attention, which she guides through her realised mind. In an aesthetic sense, she could be bone, she could be ghost. Ballerina. Blank canvas. Smoke. Conceptually she is an absent body, or a body of absence. She moves around a room full of real shadows, or shadows of the real.

LISA KELLY: Venus Figurines – Portraits of Recovery

Lisa Kelly weaves ancient feminine iconography into the recovery stories of contemporary women. Kelly’s artistic practice is greatly influenced by her background in Psychology, and is thusly concerned with the reparative potential of art. The placement of her works in the same space as both Juno Toraiwa and Ellie-Lea Jansson’s works accentuated the strong messages of empowerment in all three works. The gold leaf which features prominently in Venus Figurines is an immediate visual signification of value, all the more meaningful given the post-traumatic stories which were shared with Kelly and informed this body of work. A timewarp happened throughout the house between Kelly’s work in the open space and Harrison’s in the kitchen. Both works are concerned with iconography and symbology, however both translate and articulate their respective images into a contemporary visual vocabulary. By using block printing, rope and paint to create her images, which she then digitally printed, Kelly translates these images from an analogue medium into the digital realm. This means that the conceptual reimagination of old imagery into a contemporary context was further emphasised in the work.

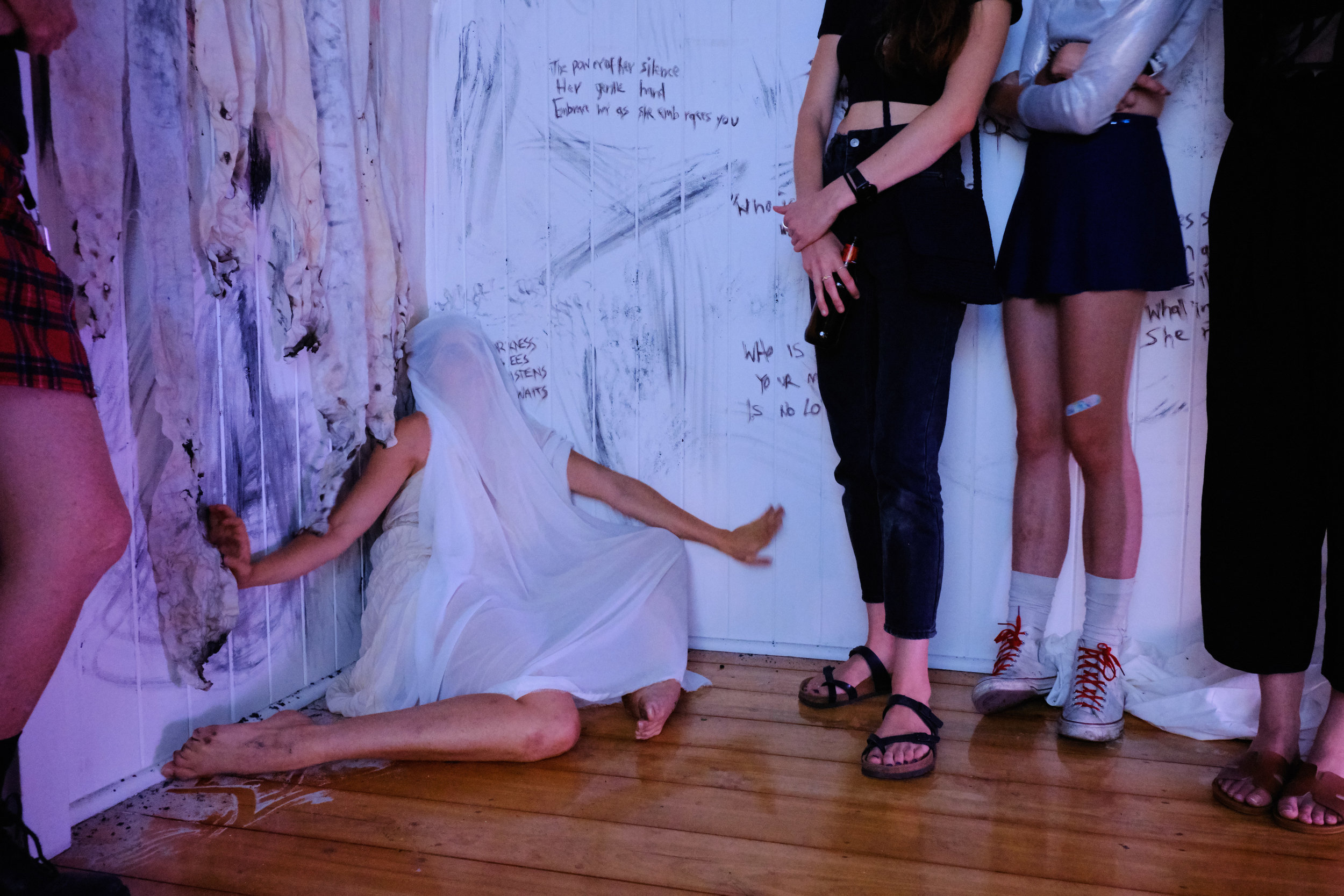

NADIA MILFORD: M A I D

In her performative installation titled M A I D, Nadia Milford adopted the ancient identity of the Mermaid. The Mermaid permeates mythology and folklore as desirable yet dangerous entity, creature of the water, goddess of an unseeable and unconquerable realm. She is thusly powerful, in her unknowability, in her indefinability. The duality of her body, at once something piscine and anthropoid, situated this being in a world of her own, and projected images of terrestrial nature further complicate this realm. Poetry scrawled on a wall in coal marked the room with the Mermaid’s personal presence. Milford redressed the concept and definition of power by studying how it can exist in this mytho-aquatic world. She blurred its physical, philosophical and psychic manifestations, repatriating it from the hands and pockets of a select few, back into the masses of the masses. Milford’s mermaid identity manifested this democratised empowerment by interacting with the audience members in the room, making eye contact with them, but also moving them around the room her own body territorially. In this underwater world, power was a natural element in each body, a thing which each body had the volition to express physically, poetically, sensually, intellectually, abstractly, deliciously, aggressively, slowly, silently, should they be so inclined. Power was no longer something wielded and held over bodies deemed lesser, or inferior. Incapacitated. Darker. Different. M A I D removed the concept of power from meritocracy, religion, economy, or any other institution, and instead submerged it in an ocean of democracy and ethics, where it dissolves, disperses and starts to move osmotically. The ambient and undulating soundtrack Milford used fostered a sense of submersion and alterity.

The Ocean is an apt setting for a radical redefinition of power. The Ocean subjects each body to its tides and its currents. In this way, the body agrees to let itself be influenced by the movements of the Ocean. The body surrenders its position to its surrounding environment. Because in the water we lose our footing, we have no ground to stand firm upon. If we tried we would suffocate and die. In the water, we remember our place in the world. We remember what power really is, what really wields it.

KATHERINE MORRICE: Connection, Belonging and Presence in Place: Faces and Stories from a Changing West End

Kathleen Morrice’s portraiture seeks the social, cultural and overtly economic background of a rapidly gentrifying suburb and city, as manifest in the many faces in its’ streets. She chases what is behind the masks we wear, what is hidden just below the surface, just under the skin. Portraiture has tended to mute or erase background in order to prioritise and iconise they who occupy the foreground, the Subject. Subsequently, the viewer has nothing else to see, to witness, to afford time, admiration, critique or attention. In portraiture, background becomes a dispensable distraction, one that detracts from the main attraction rather than adding to or contextualising it. So, the Portrait Subject has no background: they come from nothing and nowhere of importance more so than themselves. An individual alone, without a background, without a place to be or a place to go. With nothing behind or beyond its own image, the quality of The Subject’s appearance carries the weight of the world, as they are the only worldly presence in the image. Imagine the affect this depiction would have on the psyche of The Subject. Their image, immutable, and executed with the purpose of being visual appealing, hung in elevated positions on the walls of the home. Sounds like impossible standards, to which the domestic enclosure incubates the likelihood of such mentalities becoming internalised. We can follow the trail of The Portrait from the carte-de-visite, at once a declaration of elevated social and economic standing in the mid to late 19 th century, to the posed family portrait, documentary ‘evidence’ of nuclear perfection, finally to the Selfie, the prevalence, manipulability and publicity of which latently weaponise it in a digital age. Morrice is studying what motivates us to perform ourselves so outwardly yet so insularly. These identities we present, where do they come from? From fear? From intuition? From nature or nurture? Defence or reference? Regulation or deviation? Her portraits go beyond face value in search of deeper roots and identity.

ASHLEY PEEL: R.E.S.P.E.C.T: Times Have Changed

In Ashley Peel’s mural, images of partially or wholly naked bodies used to embody the word RESPECT come from an advertising industry which has established itself upon the glossed flesh of bodies, and in so doing reduced the body to such. As pig to pork, as cow to beef; consumable. Show me where is the respect in that. The mural may spell RESPECT, but is it actually communicating this word, as language ontologically does? Is it doing what is says? By bending bodies into letters, do the bodies’ physical incarnation of RESPECT lend them its semantic significance? Do the signs become the signified? Do they verb-alise the concept, enact it in their physical and spatial articulation? The mural is offbeat, it is satire and syncopation. On the first night of the exhibition, the mural was placed along the canopied entrance alley of House Conspiracy. As visitors arrived and entered the property, they were met with this word to linger in as they moved through it, and to linger on during the night. On the second night Peel’s mural appeared on a wall in the garden space, where it dialogued nicely with the physio-linguistic elements of Renee Poli’s work, without either work losing their particular conceptual space. Peel permitted offence and disagreement by inviting viewers to interact with and even destroy the mural if it wasn’t to their liking, verging the audience’s potential intervention between censorship and vigilance. Interactivity created a silent and ongoing conversation between audience and artist, balancing power between the two. This power dynamic was also present in Chance Collective’s immersive installation Nest.

RENEE POLI: soda rot riot

Poli’s intuitive practice is at the crux of her poetic, sculptural and performative work. For soda rot riot, Poli filled the garden with objects and words gleaned from her surrounds and reconstructed them into unprescribed forms, creating mysterious and suggestive symbols for the audience to experience and translate originally. A broken mirror in the middle of the garden brought the sky into the ground, like another dimension that could spill out around you, or you could fall into. By moving around the mirror, crouching down to it or leaning over it, the audience were the ones to give the mirror’s surface depth by finding themselves and other surrounding objects inside it. Concrete blocks, Styrofoam, plaster and various tubing was placed in the garden and responded to its natural impressions. Many of these objects were partially covered in fluorescent pink spray paint, which acted like a common birth mark or unifying feature between otherwise disparate objects. For her live intervention in the space, Poli used her signature pink to spray poetry and phrases onto the walls of the garden, so overlayed that deciphering the words and meaning became effortful. The use of pink turned the words into other sculptural objects like the concrete and Styrofoam. Or perhaps conversely, marking the objects in pink imbued them with the poetic significance of Poli’s words. Both of these interpretations are equally as pleasing, as is the sensation of indeterminacy between the two. Just as the object-sculptures require physical engagement, the audience has to actively think, read and move with Poli’s poetry in order to experience it. The line between physical objects and words begins to fray, an echo through Triple AAA from Asheley Peel’s mural. On the second showcase night, Poli invited audience members to smash and rebuild elements of her sculpture with her, complicating the authorship of her piece and extending its performative capacity.

JUNO TORAIWA: A Woman, A Table and The Wolf

Rather than using a strict choreography to dictate and regiment each movement, Juno Toraiwa followed organic and intuitive movements to amplify a grounding thesis: the active rupture of suppressive domesticity. The table on which she moved was an eloquent symbol for the restrictive conditions of a nuclear home that so often yoke feminine creativity and wilderness. It’s height and edges inflicted a limited and limiting environment to which Toraiwa was bound. The table is also the site of feasting, of decadent consumption. The presence of a body on a table harboured cannibalistic imagery, if only in an abstract sense. Did we substitute the dinner knife with our gaze, consuming the performing body instead with our eyes? Or did the volition of Toraiwa’s performance put the spectator on the right side of the fence? Like all art, it depends on us, and what lens we bring to the table. Tabletop dancing also carries erotic, provocative or libertine connotations. Toraiwa toyed with the duality of entrapment and empowerment, her movements oscillating between elegant, elongated forms and erratic movements. She moved between loud, thumping actions to delicate, diminutive gestures. All of these coalesced into what felt like a continuous and prosaic performance. Intuition played a big part in this, but Toraiwa was keen to emphasise the presence of intention and practice in her work. She has an idea of where she wants to move and how she wants the piece to develop, but knowing how to execute one’s desires consistently and to aesthetic effect means putting a lot of effort into honing those abilities. For Toraiwa, channelling raw emotion through learned, collaborated and refined skill into improvised dance is akin to the creative process of improvised music. She strives for continuity and fluidity, to let her mind flow into her movements.

I acknowledge the Jaggera and Turrabul people, traditional owners of the land on which House Conspiracy operates. I pay my respects to their elders’ past, present and emerging, and to their strong and ongoing culture of art, sharing and learning. I would like to thank all the artists, visitors, curators, documenters, poets, friends and House Conspirators for making Triple AAA what it was.

Ellie-Lea Jansson

Curator and Feature Artist

Ellie-Lea Jansson practices as an Artist, freelance Curator and Creative Director; ricocheting between formal and informal frameworks. The installation work produced for Triple AAA elucidates how domestic space and associated societal role expectations influences an individual’s self-concept and psyche. The psyche manifests itself within movement and physical interactions with the spaces we inhabit. The work Safe Space exploits the situational domestic environment within content and installation to reveal its capacity to suffocate the instinctual self and to be renegotiated as a territory for reclamation.

Influenced by Dr. Clarissa Pinkola Estes text Women Who Run with the Wolves, Ellie-Lea uses intuitive and spontaneous movement to take ownership of the domesticated woman and connect to the untamed, rejecting the notion of the home as a ‘safe space’.

Lisa Kelly

Assistant Curator and Partner Artist

Lisa Kelly is a multidisciplinary Vietnamese-Australian artist with a background in Psychology. While currently studying a Masters in Social Work, Lisa has held art workshops, worked as a freelance artist and has exhibited work in Brisbane throughout both her social science degrees. Drawing from her studies, her artistic practice gravitates towards themes of nature and humanity and attempts to discuss the intersection of art, mental health, and recovery. Her works feature recurring elements representative of the power in the female form, cycles of the moon and the ebb and flow of nature's pace. Her mediums include pencil, acrylics and gold leaf and span across mural work and illustration.

CREDITS:

Click on Names for Profiles

Artist in Residence: Chance Collective

Partner Artist: Heidi Harrison

Partner Artist: Justine Bootsorion Keim

Partner Artist: Nadia Milford

Partner Artist: Renee Poli

Partner Artist: Ashley Peel

Partner Artist: Kathleen Morrice

Featured Artist: Juno Toraiwa

Featured Artist: Lisa Kelly

Featured Artist: Ellie-Lea Jansson

Showcase Writer: Indy Doumenc-Medeiros

Creative Director: Ellie-Lea Jansson

Documentation Photography: Ethan Bourke

Documentation Photography: Joseph Lynch

Curatorial team: Lisa Kelly